© Saulius Aliukonis

© ROTE NASEN Clowndoctors

In Austria, some of the participating clowns changed during the course of the ClowNexus project.

However, the research and development approaches were maintained by those who replaced them.

This description of the “tools in practice” focuses on accounts of the artists Christina Matuella, Ingrid Türk-Chlapek and Sara Zambrano.

Christina and Ingrid both have 29 years of clowning experience, having started working with RED NOSES Austria in its first year of operation.

Sara comes from an acting background and has 23 years experience, 7 of which were spent clowning.

The participating artists are part of two different regional teams, in Tyrol and Carinthia.

The ClowNexus visits took place in two long-term care homes specialising in caring for people with dementia in the Carinthia region, namely MaVida Park Velden and Haus Martha in Klagenfurt.

In addition to her role as healthcare clown, Christina is also the Regional Programme Manager for RED NOSES Austria in Tyrol.

Red Noses Austria’s Research and Learning Manager Simone Seebacher, and later Katharina Lessiak, supported the Austria-based artists throughout ClowNexus with research and learning tools.

The duo started their work by researching which homes were best suited for the collaboration. With support from the Research and Learning Manager and guidance from the consultant, who at the beginning of the project developed a Baseline Study, the clowns applied some research tools including observation check-lists and questionnaires to identify the care homes to visit and the residents to work with there.

They visited the same group of seven residents per home, with some alterations due to the homes’ population changes.

Despite coming from different regions of the country, the duo worked together, visiting two long-term care homes in Carinthia.

Once the homes were selected, the artists contacted the two homes to explain the concept.

One of the homes was already being visited by healthcare clowns whereas the other was a new location, and it took some more preparatory exchanges to build the trust and rapport needed for this kind of in-depth cooperation.

The clowns worked with the selected homes for the duration of the project, phasing out visits at the end.

Both of the homes visited by the duos agreed to host a filming crew who were recording footage for the ClowNexus documentary.

Some of the residents and institutional and family carers were interviewed about their experiences.

The homes also accepted visits from the researchers conducting the ClowNexus Final Evaluation Report. This openness also illustrates the rapport and trust built with the institutions and their staff by the artists.

The staff in the homes facilitated access for the clowns to speak with family members of the residents, to identify residents they would work with.

The staff and relatives of participating residents wanted to be part of the process of creating the dynamics for the clown visits.

The clowns worked with them every two months to develop 15-minute interventions. The clowns would then invite the family members to be present during the visits that were based on the co-created scenarios.

The interventions were followed-up by common discussions in a nearby cafe. The duo used a parade as the recurring frame, and the duo would present different topics/scenarios for each visit.

Through the parade, the clowns were also able to engage with other residents in the home, who would see the clowns in the common rooms.

Staff and relatives were also consulted using learning tools.

The artists used an observation checklist for the people observing visits to fill out what they noticed during the visits.

Relatives and staff were also asked to fill out questionnaires. The questionnaires included parameters from the baseline study like observed mood; stress level; attention focus; physical behavior and connection/relationship with the clowns and others present in the room.

From observations about the results of using the questionnaires, the clowns observed that the questionnaires with relatives were more impactful for their work, possibly because the relatives have more of an emotional connection with the residents.

The artists also learned from self-reflection and filling out post-visit forms themselves, the success of the chosen theme and the tools used during a given visit.

This learning tool was further applied with the multipliers (see needs and impact of healthcare clowning organisation below) who the clowns trained and reflected with after each International Artistic Laboratory.

People with dementia – The needs of people to be visited by the clowns were discussed already in pre-selection interviews with family and staff, and further analyzed after performances with institutional and family carers.

In terms of impact, the clowns’ visits and the tools they used were observed to bring back memories, interest people to join organised activities, and engage their senses.

In the scenario described below, the flute and snake dance drew particular attention and excited the participants, including relatives who were happy to see the excitement of their loved ones.

Clowns recalled many people wanting to touch and even kiss the snake in greeting, especially as the snake was connected to a song that incited memories.

Institutional carers had the need to participate in the creative process, engage eager family members and work together with the clowns on the approach of the clown visits.

They also had the need to learn more about how healthcare clowning works, as illustrated by their willingness to fill out observation check-lists and post-visit form questionnaires so the clowns could use this information when planning their subsequent visits.

In terms of impact, the care staff were inspired by the clown visits, which also provided a break in their difficult daily routines.

Family carers have the need for more opportunities to connect with their loved ones, see them cared for and happy, aware of and engaging with their environment.

Through observation and questionnaires and interviews with relatives, the clowns observed that it was touching for them to have these moments together.

For some, seeing their parents physically active and excited brought them to tears, as they hadn’t seen them like this for long periods of time.

From the discussions, the family carers really appreciated the gift of time dedicated to their loved ones.

Clown artists – For the artists, the co-creation that took place in the project, the possibility to engage with the milieu of the persons they visited, and to really research and reflect gave hope, power and appreciation.

Regular meetings between the clowns and the Artistic Lead, help from the RED NOSES International office and the RNA Research and Learning Managers was important in the clown’s journey.

Overall, the clowns shared big learnings from the research being and were glad to have participated.

The greatest gain singled out by one of the participating artists was gaining trust coupled with risk – the risk of really getting involved with everyone from the seniors to their families and staff, and themselves – the clown and person behind the clown – always with the high goal of changing the moment.

Healthcare clowning organisation – RED NOSES Austria had already experienced clowns working with people with dementia, but not so in-depth including the reflection with relatives and staff.

The organisation really embraced the opportunity ClowNexus presented for multiplying learning across the different regions of operation.

After each of the three International Learning Laboratories on working with people with dementia, the participating duo held workshops for RNA’s so-called networkers or multipliers – one clown from each region – to share what they learned, observed and co-created together.

The colleagues would then bring the training knowledge back and bear responsibility for sharing it with their colleagues in the regional teams.

ClowNexus-inspired principles like co-creation, research of artistic tools to use with specific participants, which therefore transpired to the whole of RNA.

Below follows a description of one of several scenarios developed by the duos in Austria.

The artistic tools featured in their work rely a lot on musicality and playing instruments; ukulele, flute, guitar, and singing songs.

The duos also used movement and dance, storytelling, puppetry, creating with objects, using various props including such that engage the senses.

Scenario in Focus: Journey to the Orient

Why interesting: The scenario is both exotic, representing a faraway experience, but also invokes familiar sounds and music. The scenario is a collection of three gifts/surprises by the clowns to the participants – the song “Café oriental”, sand of the desert, and a secret in the suitcase brought by the clowns.

Intention: To invite residents on a sensorial journey filled with gifts and surprises.

Who participates: Seven people with dementia per home, institutional and family carers if present, and, more passively, other residents who are in the living room area or see/hear the clowns entering and leaving with a parade.

Duration: 20 minutes

Setup of the space: The scenario takes place in the living room area of the homes, in a quiet corner of the room. The residents being visited are seated around, other residents are also there, further away from the performance.

Artistic skills needed: Knowledge of the used songs, ability to play ukulele chords, puppetry, duo-clown-play, playing the flute

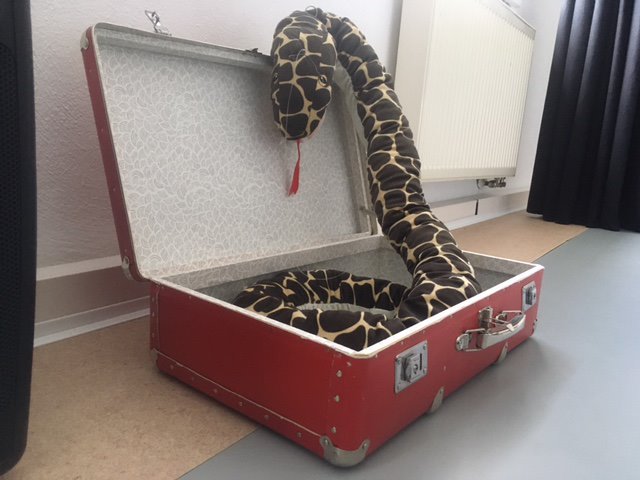

Props: Letter, a snake in a suitcase, two flutes, a bucket full of sand, a ukulele.

Description: The journey starts with the clowns, suitcase in hand, entering with a parade and a song – “Café Oriental”.

The clowns then greet everyone in the audience, introducing the topic.

The clowns would then proceed to share the gifts they brought to simulate the desert experience.

Knowing that harmony is an important part of the visit, since the visitor does not have to decide who to look at, this visit also had a part dedicated to the couple structure of competition.

The conflict in the story is the desert sheik falling in love with one of the clowns.

She receives a love letter – which contains the lyrics of the old hit “Cafe Oriental”. This provides a nice opportunity to repeat the song solo.

A nice focus – and a nice reaction of disappointment and anger comes from the second clown. Emotions provide a beautiful playground for the scenario.

After the song, the clowns bring out a bucket of sand to also stimulate the senses. The final gift in the sequence is the opening of the suitcase and the emergence of a snake.

The snake dances to the flute, played by one of the clowns. After greeting each of the residents and letting them touch it freely, the clown lures tha snake back into the suitcase.

The clowns then close the visit with the same song.

Grief became a big topic when working with people with dementia – During a separate workshop in Barcelona, the grief maps the artists worked on had a big impact on the clowns.

Working with individual grief and the grief of others was something new and something they would like to continue in the Austrian national organisation.

Family members are an important beneficiary too – The co-creation with family members led to the realisation that they valued more one-on-one encounters whereby clowns would individually visit the older people in lieu of showing the scenario to the whole group.

This led the clowns to change their approach from visiting the group together, to individual one-on-one sessions with the residents and their family members.

The family members found the group setting less inviting to participate and found it offered fewer possibilities for them to connect with their loved ones.

On the contrary, individual visits of the clowns and the scenarios they brought created a possibility for a common direction and experience with their loved ones, a soothing engaging experience like those they’ve experienced before and had few chances to relive after their family members were institutionalised.

Working in a group setting was important for the research method – The clowns started their research working with the selected seniors in a group setting, not least because they would then collectively get feedback from staff and family members present through questionnaires and sometimes discussions.

The clowns would then present findings from their research to the family members and staff, and talk about how they would take the feedback into account when further developing their approach.

For example, the switch from group to individual visits, also as a thank you for their participation in the co-creation process through the gift of time.

Learnings from a group setting transfer to one-on-one visits – From the group setting the clowns learned to use a mini-format.

It would start with music – to give residents time to adapt to the clowns’ presence.

The clowns would then slowly focus on the topic of the day, which was always changing, in three steps: something visual, something to smell, and something to feel, mostly supported by a familiar song.

The clowns engaged the sense of taste only with prior permission.

Wonderful feedback from relatives was that even if their loved ones couldn´t remember what happened one day later, it was visible, that when their loved ones heard the clowns entering with music the next time, there was a smile and a different tension in their bodies.

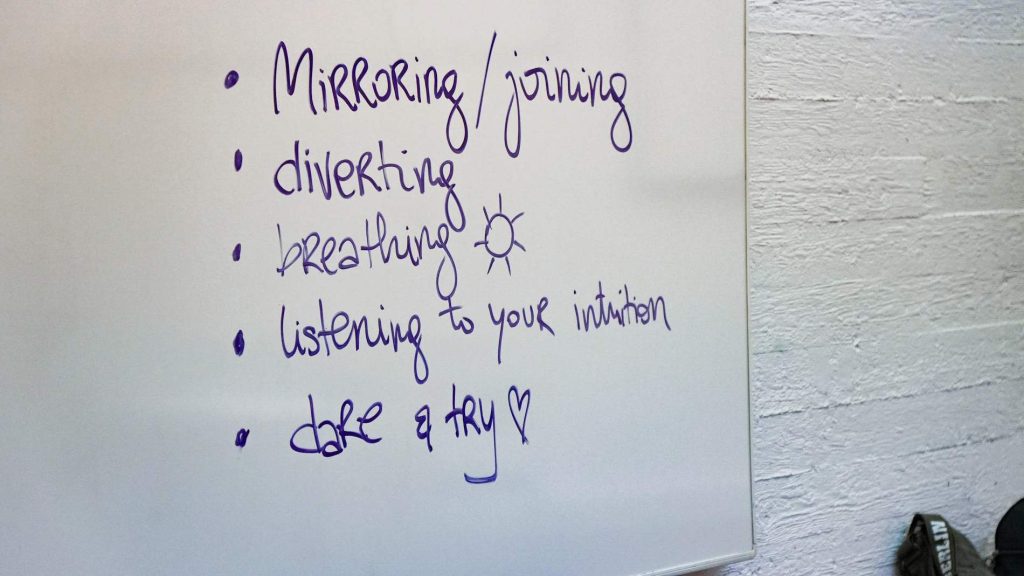

Things that resonated from International Artistic Laboratories. The AMIC framework and ‘frames’ to use when working with people with dementia taught in one of the International Artistic Laboratories by Magdalena Schamberger were among the highlights for the Austrian artists.

AMIC stands for Acknowledge, Mirror, Improvise and Challenge, and it describes the process an artist can go through during their encounters with people with dementia.

The Challenge aspect resonated well with the exploration with taking risks during the project.

The clown’s carry the ‘you are enough’ learning from the same lecturer. As expressed by one of the participating clowns:

“If we really manage to recognise the situation and the person and make a connection, a lot of things are possible – and everything is there. Also the possibility of change through a risk that enriches the lives of the residents and gets them out of their sometimes seemingly stereotypical behavior.”

Select objects carefully – While the snake in the Journey to the Orient scenario was a great hit with many people, it triggered a fear of snakes for one of the residents visited.

The lesson learned here is when experimenting with objects and materials to use in specific formats, it’s good to run them by family and institutional carers ahead of time to ensure they are appropriate.

At the same time, another lesson is that staff may not know the individual residents, especially non-verbal ones enough, to be aware of specific dislikes and fears, again pointing to the importance of exchanging with family members when developing artistic approaches.

© Emmi’s home, Turku

Elina Selamo and Janna Haavisto are healthcare clowns working with the Finnish Hospital Clowns Association, Sairaalaklovnit ry, in the regions of Kuopio and Turku.

They each have 11 and 18 years of clowning experience, respectively.

Working separately in their respective regions, Elina and Janna developed their own approach, tools, and scenarios for working with people with dementia in the course of ClowNexus, with the support of Sairaalaklovnit’s Artistic Responsible, Kaisa Koulu.

They worked both in pairs with other clowns and individually, each in different long-term care homes specialised in working with people with dementia.

In Turku, the homes to visit were identified with the help of the Alzheimer Society of Finland, which sent out information about the project to long-term care homes, inviting them to participate in ClowNexus by hosting the clown visits and the co-creative approach.

Three privately-owned homes replied to the invitation, and the clowns visited all three of them, totaling 26 visits, mostly as a duo, and sometimes solo.

The homes varied in size, housing from 36 to 100 residents.

In Kuopio, the clown artists contacted public long-term care homes with an invitation to host clown visits, and one was interested and selected for cooperation.

The home is a service housing facility where residents live in their own rental apartments and receive visits from home nursing carers.

The participating clown artists, most often working in a duo but sometimes solo, visited this home eight times during the spring and summer of 2022.

They interacted with a mix of the same and different residents, seeing people from once to five times.

Both artists frequently engaged with the staff in the homes to reflect on their work, particularly as working with seniors was a relatively new area for Sairaalaklovnit before the ClowNexus project. Giving names to the tools and approaches they were developing was a useful step in gaining confidence in the project and with this target group. An initial challenge, given the novelty of working with long-term care homes for Sairaalaklovnit, was identifying homes that were not only interested but motivated to engage in the co-creative work envisioned in ClowNexus.

© Red Noses International – Miloš Vučićević

The artists used direct observation checklists and post-visit forms with staff and their own self-reflection to learn about the changes their work contributed to.

Deeper co-creation was possible in one of the homes, which is also the residence of the mother of one of the participating clowns – the staff would send pictures, share information with the clowns, and most highlights in this particular home happened thanks to the information sharing.

For people with dementia, the artists were able to observe various ways their encounters with visited seniors impacted them.

In the examples of the mirroring exercises described in this Artistic Scenario, the artists observed that the seniors they were engaging with became more relaxed in the shoulders and face, with eyes more open and clearer verbal communication than they typically exhibited.

In both instances, the mirroring technique through physical – speechless – play developed into a verbal exchange, including an open expression of gratitude by one senior.

Institutional carers – Through participation, even if passive, in the clowns’ encounters with the residents, the staff got to share in the energy changes in the room.

Family caregivers – The Finnish clowns had the opportunity to engage more with staff in the co-creation process, as family members were less available for encounters.

At the same time, in both Turku and Kuopio, clown visits unintentionally reached family members.

In Turku, one of the clowns visited a home that is also the residence of her mom, making her both the artist performing the intervention and its beneficiary, as the daughter of one of the residents being visited.

Visiting her mom in this role was the highlight of the project for the participating clown.

In Kuopio, the clowns visited an old man living with his wife, whom they always met together. In the words of the visiting clown;

“I think the clown visits were ‘something different and refreshing’ in her daily life. The wife also got a possibility to tell about their life, and I remember she enjoyed when clowns were singing or reading poems. She was also singing along with familiar songs.”

Clown artists – The participating artists had a need to experiment with and learn about artistic tools to employ when working with senior people in general and people with dementia specifically.

They tried out a variety of them – different variations on mirroring, entering with music, working with frames such as mirroring only hands or moving shoes, traditional hand clapping games typically played with children, active listening of verbal and non-verbal language, and mirroring that.

From the observations the artists shared on these explorations, a deep reflection is evident on aspects that worked better or less well.

The artists also embraced the ethos of risk-taking as part of the journey of discovery of the clown and its capabilities.

Healthcare clowning organisation – Sairaalaklovnit is an association of regional healthcare clowning chapters in Finland and was relatively new to working with older people.

Before collaborating as part of ClowNexus, they did not have experience working with long-term care homes, meaning they had no network or know-how within the association on establishing relationships with homes and developing approaches to work with older people.

As such, there was a lot of outreach work, learning, and exploration in this process, supported by the international learning and sharing that was at the heart of ClowNexus.

The Association really embraced this work, and as of autumn 2022, following an informational workshop for the Sairaalaklovnit clowns by the ClowNexus duo, the whole association started working with older people, with and without dementia.

The regular and nationwide clown work with older people was made possible by a major grant they received from the Funding Centre for Social Welfare and Health Organizations (STEA), a Finnish state-aid authority operating in connection with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

In the grant application for this project, Sairaalaklovnit highlighted the learning from ClowNexus and the pilot visits.

© Sairaalaklovnit – Amanda Aittamäki

Scenarios in Focus: Mirroring and mirroring hands.

Why interesting: Mirroring is a common approach used by healthcare clowns and received some attention in the workshops facilitated during the International Artistic Laboratories in ClowNexus.

The Finnish artists’ use of mirroring, including a specific focus on mirroring hands, in their respective regions and in different contexts, showcases the strong possibilities this simple approach offers for making a connection.

Intention: To connect; to play; connect to others through play; to activate the residents and invite them to move, including in small ways; to invite people to come out of their bubble.

Who participates: The scenarios involved residents – people with dementia, the clowns, and other residents and staff as observers. Active participation ranged from just one person to several, in the provided examples.

Duration: The mirroring exercises lasted around 15 minutes and can be extended to longer periods of play.

Setup of the space: Both artists worked in long-term care homes specialising in care for people with dementia.

For the general mirroring exercise, the setup needs to allow for a clear line of vision between the clown and the resident. For the hand mirroring exercise, a resident seated at a table works well. Both artists used this approach in the common area, accommodating the residents where they are.

Artistic skills needed: Mirroring; movement; sensitivity to sense the people; patience; ability to keep one’s artistic mind interested and playful; repetition.

Props: For the hand mirroring exercise, a table is helpful but not necessary.

Description: Below follows a description zooming into a specific experience of using mirroring hands by Janna and Elina.

The clown was standing and interacting with other residents sitting at the dinner table.

A resident came into the room and said hello. The clown turned towards him and made an exaggerated hello with her body.

The resident mirrored her movement. From this, the clown took the impulse of the mirroring game and started suggesting simple movements for the resident to copy.

The resident picked up the game instantly. Slowly, the game continued so that no one was leading the game, so to say.

The clown also took a little risk by suggesting more energetic movements which led to the resident suggesting boxing. In the end, they had a few minutes of air boxing together.

The clown didn’t want to continue the fast movements for too long as she wasn’t sure about the resident’s balance and fitness.

The clown stopped the game by announcing the resident as its winner by lifting his hand up, as in the boxing games, and led him to sit down.

Then the caretaker offered him a glass of juice to refresh from the movement. After drinking, he started to talk more about his boxing experience and other sport memories to the other clown who was sitting at the table.

It was a solo workday for Elina, and she had a group session in the common living room, including music and singing.

The artist was about to leave, and one lady waved her hands as a goodbye. For some reason, the clown started to mirror her waving, and they developed a waving dance together.

At first, the pair had quite a long distance between them. Gradually, the waving changed to both hands, and they were playing with the size and quality of the waving. The lady was sitting in one spot the whole time, and the artist was gradually moving closer to her.

In the end, the two had physical contact with their hands. When done with the dance, the lady looked the artist in the eyes and said, “thank you, you accepted me.” Then they said goodbye.

Repetition, eye contact, small changes, and simple movements are key – a common learning across the variety of artistic tools tried out by the healthcare clowns in ClowNexus for both target groups was clarity of communication – verbal or not – through a clear intention, repetition, and not overcrowding with additional stimuli.

Always on your time – likewise a common learning for various artists in ClowNexus is the importance of giving time for people to react, on their terms.

Giving time for the participants and going into their world instead of expecting them to adjust to the clown’s world and pace was among the learnings of what worked for the participating Finnish artists.

Likewise, and on the flip side of this, was a learning to consciously work to slow down the clown’s ‘pilot’ who is constantly offering impulses of things to suggest in a given game – this, when a participant can’t keep up, can trigger them to shut down and disengage from the game.

Human interaction is much more about being present and hearing, and not about understanding the words – this learning is a direct quote from a reflection of one of the participating Finnish artists, and illustrates that the clown with all its empathy and capabilities is well-placed to hear and be heard by people of different abilities, even if no language, or a different language is involved.

This learning came from a scenario where the clown used mirroring to help her come down after being triggered by a waving red scarf in another clown’s performance to relive a difficult experience.

The clown’s subtle mirroring, whereby they accepted the woman’s upset mood, listened to her speaking in her own language, and really understood the emotions there while kneeling at her side, led to her calming down and even laughing at the scene that resulted with the clown.

Risks are risky but can be impactful – in the same example with the red scarf, though effectively a ‘dangerous’ symbol that may be avoided in the healthcare clown toolkit, its use in the scenario evoked a reaction, even if with a negative mood, an episode of verbal communication.

In other instances, the clowns were not able to evoke a reaction from this resident. The important caveat is that the clowns were there to turn around the reaction their own scenario produced to a pleasant one for the participant.

© Pallapupas Spain

Ricardo and Núria are experienced healthcare clowns working with Pallapupas, a healthcare clowning organisation in Catalunya.

As part of ClowNexus, they worked with Fundació Pere Relats, a non-profit care home that caters to people with dementia. They had been visiting the home for around a decade before ClowNexus started.

During the project, it was one of several homes where they had the opportunity to engage in regular and in-depth work with individuals with dementia, as well as with their care staff and families.

The home was selected because the administration enthusiastically received the clown visits and the EU project, and gained confidence in healthcare clowning approaches.

The administration’s investment into the project was further confirmed by the home agreeing to host a group of visiting clowns in an International Artistic Laboratory that took place in Barcelona, and later also observation visits by evaluators.

At Fundació Pere Relats, a multidisciplinary team filled the clowns in on the latest developments of the residents prior to each visit. The duo also sometimes got to see family members who visited the centre frequently.

People with dementia

For the residents, there is a need for stimulation in their daily routine. It’s important for them to be engaged, included in games and connected with other residents, staff and visitors.

Activities such as the parachute game described below, also proved very favorable for engaging the senses – where beyond visual stimulation people can touch and feel movement from their own and others’ impulses.

Impacts observed by the artists were increased feelings of joy and fun among the residents; changes in mood and activity levels from passive to being more cheerful and lively; and changes from low to high energy levels.

Institutional carers

For the staff in the home, there was a need to connect with the residents, find ways to engage and experience new ways of interacting with them. The clowns observed the staff’s enjoyment and engagement in the activities, including through physical activity e.g. jumping.

Clown duo

The clown duo had a need to find their feet in the new project, and they mentioned the International Artistic Laboratories as something that supported their journey considerably.

The clowns developed new ways of working and a deeper appreciation for the needs of older persons and persons with dementia specifically, as well as the people surrounding them.

Their ClowNexus experience was accompanied by feelings of gratefulness, increased self-reflection and an expansion of their comfort zone.

Furthermore, the connections built with the residents and staff were a reward for the duo.

Healthcare clowning organisation

Pallapupas has been working for many years with geriartic programs, specifically with people with dementia, and has had a long-standing and deep cooperation with Fundació Pere Relats.

ClowNexus provided the opportunity to investigate and explore, through co-creation with staff and family, creative approaches to reach people with dementia.

A golden opportunity emerged for the artists to grow, improve and critically approach their methods.

Thanks to the collaboration of different paths, work systems and experiences from other countries during the project, Pallapupas, the participating artists and creative managers could dedicate the necessary time and focus to this work.

The organisation aimed to advance their intervention with older people in residences and social-health centers to be able to integrate healthcare clowning into the health system of older persons.

Pallapupas is currently advocating for a model of care that is better for the users, but also preventive, effective, lasting and efficient within the social care system.

Therefore, Clownexus served as a source of knowledge that will allow Pallapupas and participating artists to further their cause.

The duo used a variety of artistic tools including movement and slapstick, conscious use of space, creating with an object, and playing with voice and sound.

Scenario in Focus: Flying with a parachute

Why interesting: a parachute is an object with a clear purpose that is recognisable and easy to relate to.

Its use in the living environment of the residents, allowed the clowns to transform its meaning during the artistic encounter.

The parachute, an object that represents movement and flying, sparks the imaginary and fantasy realms and helps residents to transform and surpass the possibilities of the home’s living room.

Intention: To disrupt the space, create a relationship

Who participates: Residents, staff and relatives who are present, and the healthcare clowns

Duration: 2-2,5 hours

Setup of the space: The clowns and staff, and others who are present at the time of the visit, fly the parachute in the living room – a big common area used by the residents of the home.

The residents are around it, partaking in the activity and holding the parachute, touching and moving the additional soft objects that sit on the waving parachute.

Props: The parachute, various soft objects, table, fans under the table (see phase 2).

Description: The parachute game can take up to two hours or longer, and it involves a process of building up, as described below.

Phase 1: Everyone is seated around the parachute which is supported by people around it. Initially, the attention is on each resident individually, allowing each one to engage, touch the parachute, and then move on to the next person.

The pilot of the parachute is also in the game, directing attention to the other flyers. The soft movements of this object with each interaction awakens people’s attention and interest.

Clowns invite the audience to play by throwing soft objects on it or just simply having fun by observing how others react to and interact with the game.

The clowns are sensitive and attentive to reactions around the parachute and build up the play accordingly.

Phase 2: After letting the parachute hang in the air while being held by those around it, the clowns put a table under it and one clown lays on it.

This aspect in the game resulted from a recurring focus in International Artistic Laboratories for clowns to explore taking risks.

The risk in this case was a physical one, whereby the clown lying on the parachute, which is supported by the table, is able to fully rely on the structure and take flight.

The allusion to flight is also reinforced by using fans under the table to make the parachute flutter. The clown’s movement, as well as movements of the soft objects around the parachute, simulates the sense of flying.

The audience gives impulses by moving the object, and the clown reacts on these.

Stimulation of the senses can go further

The clowns observed the benefits of engaging the residents’ senses, which they felt could be taken even further by including more sensorial objects like feathers and leaves, and even include sounds like wind or birds flying to go with the theme. The theme of flying could be further reinforced by the clowns wearing aviation-like costumes.

Could explore the game with people with advanced dementia

The parachute was flown in the common area, meaning only those residents who could make it there were included. At the same time, the clowns believe it could also work with people with advanced dementia that cannot attend activities outside their wards.

Togetherness helps overcome limits

When people with dementia get a chance to partake in a joint activity with relatives and staff, instead of as passive observers, they become equal participants. The clowns felt this was a transformative element, whereby the common game and sense of togetherness helped overcome limits.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaitė – NARA

Tünde Gelencsér and Andrea Kiss have 21 and 20 years of clowning experience, respectively.

Tünde is the Artistic Director of PIROS ORR Bohócdoktorok Alapítvány in Hungary and was also the artistic lead for the clown duos working with persons with dementia in ClowNexus.

In addition to clowning, Andrea is also a mental health professional and has experience working as a mental hygienist in the same long-term care institution she was visiting as an artist in this project.

Andrea and Tünde worked together to co-create the artistic tools and approaches for visits with persons with dementia in Hungary and in the International Artistic Laboratories.

However, they went on visits to the homes with other duo partners.

While Tünde works in Budapest, Andrea is part of a team working in the southern city of Pécs.

This approach of learning together and then working with wider teams was intended to share their experience in the project with more clowns in PIROS ORR.

The clowns, therefore, developed their tools together and started building up a team to cooperate with them in visits, sharing their learnings through workshops for the participating clowns.

Since hosting the first International Learning Laboratory in October 2021, the Hungarian clown artists engaged in regular exchanges with the team of clowns working on the project to exchange ideas, feedback, discuss obstacles, and emotions experienced along the way, developing their approach accordingly.

The artists pointed out that in this process, they ended up fine-tuning their approach before each and every visit.

In Budapest, ClowNexus visits took place in three homes.

In Pécs, the clown artists visited one home.

In Budapest, two of the homes were already in cooperation with Piros Orr, visited by clowns on a regular basis since 2014.

One institution was a new partner, chosen because the home has a mid-stage dementia ward and also a late-stage dementia ward. The choice of the institution in Pécs was based on an existing cooperation with Piros Orr and the support of the experts.

As Andrea is working in this institution as a mental caregiver, it was a great opportunity to work on a special program for people with dementia, inviting the staff into co-creation and monitoring the impact in the same place.

The latter was selected as a home PIROS ORR were already cooperating with the most, through a program called Hotel Sunshine – a clown-made ‘telenovela’ for persons in long-term care.

The approach there was to transform the existing program specifically for persons with dementia.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaitė – NARA

Persons with dementia – The clown artists found that they really managed to make a connection with the persons visited, contributing to changes in the mood of individuals but also an overall change in the environment in the department they’d go to.

Clown visits also acted as a connector between the people in the wards, awakening their interest in and communication.

Institutional carers – The clown artists, through the deeper-level co-creation with the institution they visited, were able to build trust with the institutional carers.

The regularity and depth of exchanges on what the clowns are attempting to do and how it works out in the individual visits developed into the carers counting on the clowns to connect with their clients, and vice versa, the clown artists counting on the carers for information and mentoring on also what they see as working and when.

In the words of one of the clown artists, “it is already not like visiting a place; it is much more like working together.”

Family carers – In the context of visits to one of the three institutions cooperating with Piros Orr in Budapest, family members, mostly children of the seniors visited, were available for co-creation.

The family members joined a clown visit and attended a discussion with the clown artists afterward to share their first impressions, feelings, needs, and also how they saw their relatives during and after the clown intervention.

Later in the program, the clown artists invited the family members again to experience a clown visit with their loved ones again.

Clown artists – Before ClowNexus started, Andrea and Tünde had been visiting long-term care homes and already felt the need to do something special for people with dementia.

The co-creation and exploration built into the ClowNexus approach resulted in a stronger cooperation with different stakeholders.

The clown artists say they feel much more familiar with the institutions they visited. In the end, this translates, for the clown artists, into more freedom to try out new ideas.

The clowns became more sensitive with their own senses, in addition to working with the senses of the people they visited, and feel the tuning made possible by the experience in the project made them more attuned to themselves as people and artists.

Healthcare clowning organisation – PIROS ORR had not only participating clown duos but also the Artistic Director with a leadership position in ClowNexus, leading to a lot of learning and sharing.

In the spirit of sharing their experience in the organisation, Tünde and Andrea facilitated workshops and presented their work with persons with dementia in Clownexus in several sessions as part of conferences and national clown camps.

With the start of visits to people with dementia under ClowNexus, the Hungarian clown artists changed their approach from visiting individuals in their rooms during geriatric visits to seeing them in groups in the common areas.

They played around with metaphors of ‘containers’ – backpacks, suitcases, and bags as containers of memories.

In Budapest, the team played with calling memories with a topic and an object that has a strong sensory impact, to also build a common activity with, something the seniors recall doing in their daily lives.

As part of the activity, the clown artists used music, children’s songs, and rhymes.

The idea behind the tools they opted for was to create an intimate connection with care home residents, who are often seated together in common areas, without having too many props.

The Hungarian clowns also experimented with ‘natural ingredients’ – things relating to nature and the seasons, to plants and fruit, references to which are in abundance in Hungarian folk songs.

Two scenarios from the clowns’ visits are described below.

Scenarios in Focus: (1) Washing Clothes and Drying & (2) It’s Raining

Why interesting: Both scenarios involve creating with an object and a mix of movements and sounds to connect participants with a lived experience from the past.

Intention: Both scenarios have connecting the group and sensory stimulation as a common intention. Also, while the “It’s Raining” routine is meant to connect people with nature and stimulate the senses; the “Washing Clothes and Drying” exercise particularly aims to tap into people’s memories of this much-experienced commonplace activity from the past.

Who participates: residents, staff, relatives

Duration: 15-20 minutes for “It’s Raining”; 30 minutes for “Washing Clothes and Drying”

Setup of the space: Both scenarios take place in the common room in long-term care homes.

“Washing Clothes and Drying” always requires a group of participants, whereas the “It’s Raining” exercise can work in one-to-one settings or smaller groups that can fit under the umbrella.

Artistic skills needed: Artists need to be skilled in creating with an object, musicality, and storytelling.

Props: “Washing Clothes and Drying” requires a washbasin and scarves; “It’s Raining” calls for a colorful umbrella.

Description:

Washing Clothes and Drying is a proposition to play a game of playing with a familiar activity, washing clothes. It starts with clowns entering the common area with scarves in a big washbasin.

The idea is that the clowns play with the “dirty clothes” – the scarves, using them for sensory impulses – washing movements with their hands, moving the scarves for drying with the flying scarves at the end emanating a fresh smell.

The clowns then invite the residents to partake in the activity – they dip the “dirty clothes” into the washbasin and start a rhythm and singing to accompany the collaborative washing.

The washing movements quickly activate people’s physical memories of this activity and connect them to the topic of the game, with music further supporting the group connection to the common activity.

The clown game then extends to the drying of the clothes, with the clowns erecting a long drying rope with clothespins for the residents and staff to use to hang the laundry.

The hanging clothes smell fresh and clean, and the group sings again to solidify their connection.

It’s Raining is also a tool focused on sensory stimulation and, in this case, a connection to nature.

The clowns enter the common area with a big, colorful umbrella. The first connection is going through the object, awakening interest and opening the topic of the rain for the participants.

The duo starts to build the play by creating sounds of nature, the wind, and the rain by blowing, tapping the objects they have, and using soft rhythm instruments.

The clowns open the big umbrella and invite the audience to hide under it. The play is better suited for individual play or for a very small group.

Under the umbrella, the participants listen to the sounds of the rain, which can come from tapping fingers on the umbrella.

The clowns then develop the play with the emotion and impulses coming from the audience.

Rain is a strong connector to emotional memories, and thus the play overall has to be very intimate and sensitive, aware, and reactive to the people taking part. The aim is to keep the intimacy with soft variations in the play.

©PIROS ORR – Vera Éder

The more time, the better with people with advanced dementia – during COVID and the changing dynamics of visits, the Hungarian clowns accidentally spent twice more time than they normally would in a visit with people with advanced dementia.

The duo finished going around the floor (clowns visit all the floors/wards in the homes) and instead of heading up to the other floor came back for one more round.

This time, instead of the first time around, the people were already high energy as the clowns had warmed them up, and it was possible to go even higher. The learning was that it worked very well to give more time to these visits.

Clowns connect and play with people with dementia through association – during the visits, clowns focused more on giving the time to build a connection.

A realisation that came from the moment when the clowns were really connected in the midst of their intervention was that the clown’s presence is free of constraints of time and connects smoothly to the associative logic of people with dementia.

The clown logic and the free association of the resident with dementia is connected in strong playfulness and creates a lot of joy. This associative logic is useful for the clown to be driven through improvisation.

How to deal with aggressive behavior – in the visits with persons with dementia, the clowns were minimalistic and simple in the approaches they employed.

The risk involved in the less artistic approaches is that the simplicity can be misunderstood, also emotionally.

An example was a situation with a woman one of the duo clowns accidentally triggered by accidentally hitting a wall during their interaction. This made the woman react aggressively, and the clowns tried to find something she didn’t react so strongly to.

The duo let her follow them while they made their little journeys around connecting to other residents. In the end, this amounted to a long journey for the woman, but eventually, she was standing calmly next to the clowns.

What worked to appease her anger was that the clowns acknowledged her authority while keeping a distance, allowing her the chance to show what she felt.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaitė – NARA

Irena Kolar Vudrag and Sendi Bakotić are healthcare clowns working with CRVENI NOSOVI Klaunovidoktori, collaborating with the Zagreb and Rijeka teams.

Sendi has 3 years of experience in clowning, and Irena has 11 years.

Irena has been working with older people since 2011 and, since the beginning of ClowNexus, she has felt a mission to bring good feelings, laughter, and love to this group.

She found her space and a desire for professional growth in working with older people.

For Sendi, her first visit to a person with dementia as a clown started with the beginning of ClowNexus. However, as Sendi recounts in this blog post, she has experience with dementia as a granddaughter of someone afflicted by it.

The clown artists were selected on behalf of the Croatian Red Noses organisation to participate in ClowNexus and focus on approaches to working with the elderly with dementia.

The pair participated together in International Artistic Laboratories as part of the project, co-created their approach to visits within the project’s framework, and went on visits together in Zagreb, despite Sendi being based in Rijeka and traveling for the visits two days per month.

They visited residents in two long-term care homes. On the rare occasions that one of them could not make a planned visit, the other would go on solo visits.

The clown artists each worked in long-term care homes specializing in working with people with dementia in their respective cities.

They selected two residences that were already partners of CRVENI NOSOVI and that had separate dementia wards.

Croatian clowns had been regularly visiting one of the homes for over 10 years.

The other home was visited by a special CRVENI NOSOVI project – clown band Ni Neki Bend – and the staff had already expressed interest in receiving regular clown visits.

This home worked well for the ClowNexus visits, particularly because they had dementia wards on two floors, providing many older people to visit.

CRVENI NOSOVI Klaunovidoktori had been visiting elderly homes since their founding in 2010.

Inside some homes, there are dementia wards, and in many of the homes, older people with dementia are present in different residential sections alongside other elderly who don’t have dementia.

For example, in inpatient care, older people with and without dementia share spaces.

The Croatian clowns met people with dementia during their regular visits but didn’t always have appropriate tools or enough time to connect with them because they were often placed in rooms with other residents.

Since Sendi and Irena’s experience in ClowNexus, they provided workshops for colleagues and will now share their learnings with CRVENI NOSOVI artists in their respective cities.

The Croatian clown artists gathered information about the people they visited from institutional and family carers.

This information included insights about the professional and personal lives of the residents, which later served as inspiration for developing and selecting tools and topics to address in their visits.

After the visits, the artists documented their experiences in post-visit reports, highlighting special moments that left an impact on their memories.

In the spirit of co-creation, a principle embraced by the ClowNexus project, the clown artists engaged more deeply with the long-term care homes they worked with. They held panel discussions halfway through the project and at the end, outside of the care homes, inviting staff members and families to share their observations and feelings about the impacts they had experienced.

People with dementia: A heartfelt recount of a daughter of one of the people visited by the clown artists, available in a video portrait here, talks about the changes she observed for the people visited by the clown artists.

From her observations, she finds the clowns act as mobilising agents for the residents who would typically be sitting alone, watching TV, or engaging in other activities.

She notes, “But when the clowns are there, it’s different – they’re laughing, they’re interactive, they’re singing, dancing, they’re clapping with their hands, it’s very nice.”

Institutional carers: The Croatian clown artists’ experience with the institutional carers in the two homes visited was genuinely co-creative.

The institutional carers extended their trust to the clown artists, sharing detailed information about the residents to be visited as part of the initial research and preparation process, and continued this collaboration throughout.

The mutual benefit was realised through the clown artists sharing their expertise in connecting with people with dementia by demonstrating it during their visits.

Family carers: The above-mentioned video portrait illustrates beautifully how a family member experienced the clowns visiting her mother.

She notes, “When I saw my mother, she was dancing and she was laughing, she was hands in the air, I was very happy.”

Overall, the Croatian clowns had substantial contact with family members, initially meeting with them to learn about the people to be visited and to understand the family members’ wishes for their loved ones.

Family members were also invited to, and some attended, the panel discussions mentioned earlier to share their experiences of working with the clown artists.

Clown artists: Irena was able to realise her mission to bring something special to her work with older people in general and to focus specifically on people with dementia.

She found her passion and expressed her wish to continue raising awareness of dementia.

She also aims to create a theater play or a book about dementia clown visits and continue to grow professionally in this field.

Sendi went from her initial visits as a clown to people with dementia to developing a deep appreciation for interacting with this group.

Healthcare clowning organisation: CRVENI NOSOVI was already well-established in working with older people.

Still, the focus on dementia provided by ClowNexus was unprecedented.

The organisation wholeheartedly embraced the opportunity to learn and share these learnings through having clowns in different cities working separately.

This enabled them to expose more people to the expertise and learning generated from the project. The participating clowns also held a four-day workshop for all interested clowns in the organisation.

They also incorporated learnings from their participation in ClowNexus into both the groups working with dementia and ASD, culminating in a larger sector event, including an exhibition and panel, in October 2023.

The event was attended by medical staff, heads of institutions, policymakers, media, artists, and clowns who experienced the type of work with the senses undertaken by the clown artists in the project.

Below is a description of one of the several tools explored in practice during ClowNexus visits by the Croatian clown artists.

The artistic tools they employed centered around musicality, transformation of the space and time, and recollection of memories.

Scenario in Focus: Oldies are Goldies Party

Why interesting: This scenario creates an immersive experience for the participating residents using mediums that everyone can relate to, namely music and a party atmosphere.

Intention: The clowns invite the residents to share in the party mood to change the atmosphere, travel back in time, recall memories, and make the residents feel beautiful.

Who participates: Residents, staff, and clowns.

Duration: The party is a process that includes a warm-up, dressing up together, and living the experience itself. The duration can be around 1 hour and 30 minutes.

Space setup: The party takes place in a common room open to all interested residents.

Artistic skills needed: Musicality, dancing, storytelling, and creating with objects.

Props: Old/loved objects that resemble the past, such as a knitted tablecloth, a portable suitcase-vinyl record player with a collection of old records, and a Bluetooth speaker for playing songs on the fly.

To get the residents into the party mood, the clowns bring paraphernalia like jewelry, scarves, and other items for dressing up.

Description: The clowns bring old objects to decorate and create a retro party atmosphere. The retro objects trigger memories and help establish a party atmosphere as the residents knew it when they were young.

The invitation is for everyone to join and have fun together. The clowns and residents dress up as they like, get in the mood by choosing beloved songs together, and co-create a party.

Listening to music, dancing, and engaging with the energy bring joy. As a party is a fast-paced environment, it is essential to adapt this reality to the participants. The clowns found it important to take the time, go step by step, and not overwhelm the residents with too many impulses.

Creating the atmosphere together and allowing participants to choose their own rhythm and pace is crucial.

The activity can evoke strong memories, so it’s essential to provide enough space for the residents to experience their emotions.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaite – NARA

Familiarity Matters: Enjoying parties is often influenced by being in the company of familiar people.

The clown artists learned that this scenario is better received when the clowns, possibly the same set of clowns, establish a deeper connection with the residents through previous visits. The residents were more receptive and festive when they had a stronger bond with the clowns.

On occasions where there was a gap in visits, like during the summer vacation period, the scenario had less success as the residents had grown more distant. It took some time to reestablish the connection, which happened through simpler methods.

Props’ Practicality: The artists discovered that there can be a disconnect between the idea and practice, not only in experimenting with artistic tools but also with the props used.

In the Oldies are Goodies party scenario, the vinyl record player and records were more suitable for decoration than for playing music. It was more practical to use a Bluetooth speaker or a personal mobile phone to play songs.

Additionally, props are most useful when someone closely engages with them, actively using them. Props can be powerful when used in this way and create memorable connections.

Creativity and Humor Persist: The artists learned that even when people face memory loss and cognitive challenges, they can still connect through creativity and humor.

These core aspects of the human experience endure, and they provide a meaningful point of connection.

A specific example of an emotional connection through creativity and humor is documented in Sendi Bakotić’s blog post.

The Importance of Regularity: Regular visits are essential, not just for the well-being of the seniors but also for maintaining the strong connection between the residents and clowns.

Gaps in visits can lead to fading memories of the clowns, and it may take time and effort to reestablish that connection.

Working in duos and sharing experiences with other teams and professionals helped during these transitional periods. International Artistic Laboratories also played a vital role in re-establishing connections.

These lessons from the ClowNexus project offer valuable insights into improving the quality of life for people with dementia and demonstrate the power of artistic tools in healthcare settings.

© Red Noses International – Miloš Vučićević

The Lithuanian healthcare clowning organisation, RAUDONOS NOSYS, part of the RED NOSES International network, had a well-established older people program and clowns trained in approaches to work with older people even before their involvement in ClowNexus.

Between 2021 and 2023, independent of ClowNexus but with support from the RED NOSES International’s Innovation Fund, they developed a novel program for visiting older people living in remote areas, known as “Clowns on Wheels.”

Simultaneously, ClowNexus introduced a dedicated focus on dementia, especially advanced dementia, for three selected clowns.

Justinas Narvydas, partnered with Severina Špakovska and Joana Čižauskaitė, embarked on visits as part of this project.

Justinas possesses 11 years of experience in clowning, while Joana has been a healthcare clown for 12 years, with the last 8 years dedicated to working with older people.

The Lithuanian clown artists and RAUDONOS NOSYS collaborated with two long-term care institutions during the project. One was a long-standing partner in Vilnius, which the clowns visited extensively in the early exploration phase of the project.

The other was Addere Care home in Trakai, a new partnership for the organisation.

The clowns dedicated most of their visits through ClowNexus to this new partner. The initial connection with Addere Care was facilitated by Joana, one of the participating clowns, who also works as an occupational therapist and had a pre-existing relationship with the institution.

The collaboration with Addere Care began with a conference in June 2022, named ‘About the Organisation and Dementia,’ where both parties co-created a set of anchoring principles focused on a holistic approach to dementia care, aligning with HM Queen Silvia of Sweden’s Silviahemmet Care Philosophy, which was implemented in Addere Care.

The clown artists conducted approximately three visits to Addere Care each month, with one visit being led by a clown duo, and the other two by solo clowns.

Additionally, they organised seasonal visits specifically for the care staff, with the most memorable being during Christmas, when clowns, staff, family members, and residents joined in a collaborative game to fulfill residents’ wishes.

This event fostered a strong sense of community and appreciation among all participants.

The Lithuanian clown artists assessed the needs of the residents in consultation with the staff, discussions between clown duos, and insights from the program manager.

In the early stages of the ClowNexus project, a baseline study was conducted using the “My Favorite Story” tool to gauge the requirements of older people living in the care homes.

People with dementia: The visits by both clown duos and individual clowns provided residents with a delightful communal humour shower, brightening their mood and offering various engaging activities.

For some older people who had previously displayed aggressive behavior, the clowns managed to break the ice and develop tools in collaboration with the staff to cope with anger and rejection more effectively.

Feedback from family members also supported the positive impact, with one family member noting that her mother felt happier and remembered the clowns after the visits.

Institutional carers: Institutional staff became well-acquainted with the clowns’ abilities and found them particularly valuable in situations where they encountered difficulties.

The clown artists’ presence inspired the staff, who acknowledged the clowns’ ability to handle complex moments and contexts.

Clowns often acted as mediators to help connect with older people who had been challenging to reach.

Family carers: Family members were encouraged to participate in the opening conference and attend clown visits.

Seasonal celebrations, such as the Christmas gift exchange, provided opportunities for family members to share in the joyful atmosphere created by the clowns and interact with their loved ones in the care home.

Clown artists: Both Justinas and Joana, who already had a profound interest in working with older people before ClowNexus, solidified their focus on clowning with older people with dementia through their participation in the project.

The experience transformed their thinking, making them more attuned to the changes experienced by the residents they visited.

They learned to pay attention to small details and were empowered to share their insights with their colleagues.

Healthcare clowning organisation: In parallel with ClowNexus, RAUDONOS NOSYS developed the “Clowns on Wheels” project, expanding their efforts to work with older people, including those with dementia.

Joana and Justinas became resources within the organisation to educate other clowns on their experiences working with older people with dementia.

They held a workshop in September 2023, sharing the knowledge they gained through ClowNexus, and the organisation conducted a closing event in October 2023, showcasing their experiences and inviting various stakeholders.

© Red Noses International – Miloš Vučićević

The Lithuanian clown artists experimented with various artistic techniques during their visits to older people with dementia.

The approaches varied, depending on whether they visited as a duo or as solo clowns.

One of the clowns incorporated music with instruments, while the other, also an occupational therapist, blended clowning with occupational activities such as drawing and handicrafts.

Rhythm, repetition, movement, object manipulation, and slapstick techniques played a significant role in their approach.

Here’s the story of one of the tools they used during their visits as a duo:

Scenario in Focus: Train to the Seaside

Why interesting: This scenario employs the concept of a familiar mode of transportation, evoking sensory memories such as the sounds of a train station, the wind from an open window, and the smell of the sea.

The journey framework provides a clear storyline while allowing improvisation and engaging multiple senses.

Intention: To transport participants into a sensation of traveling, evoke memories of past journeys, stimulate their imagination, and bring the joy of adventure.

Who participates: The clowns facilitate, and a group of older people take part, while staff can observe and join in the activity.

Duration: The activity typically lasts between 30 to 50 minutes, considering older peoples’ attention spans and needs.

Space setup: The journey takes place in the common area of the care home, or outdoors depending on the season. Participants are arranged in a circle or as they prefer, with flexibility to move during the activity.

Artistic skills needed: Musicality, rhythm, storytelling, and clowning.

Props: A ukulele for music, a suitcase to enhance the travel experience, and a large blue fabric for simulating the sea.

Description: The clowns enter the common area, playing a melody suited to a seaside trip, and simulate the sounds of a bustling train station as they move through the audience, creating an appearance of being in a hurry.

Their rush is amplified by slapstick elements and comedic mishaps that impede their progress.

Eventually, they make it onto the imaginary train, ensuring all participants are accounted for. They play out the train journey, complete with stops, restroom breaks, and train sounds.

Upon “arriving” at the seaside, they unroll the blue fabric, inviting participants to touch and feel the “sea” and engage their senses.

The day trip concludes with a return to the train station and a train ride back home. The clowns exit the common area in the same playful manner they entered.

© Saulius Aliukonis

The significance of dressing up: The clown artists noticed that their apparel not only influenced their demeanor during visits but also played a vital role for the older people.

Residents paid attention to the clowns’ attire, and it became an artistic tool and an invitation to play.

For instance, Justinas’ choice of loose-fitting clothing often led to humorous interactions with residents.

The clowns adapted their outfits according to seasons and holidays, such as dressing as Santa and his helper during Christmas.

Humility and honesty are effective: The clown artists learned that staged approaches to capture residents’ attention, such as rearranging furniture, were less effective than allowing interactions to flow naturally.

Being in the moment and taking time to build relationships without forcing artificial changes yielded better results.

Adopting clownish approaches: Older people often appreciated the humor in clowns’ behavior, even when they set playful conditions, such as the lady who awaited their visit in her Sunday best.

Older peoples’ willingness to participate humorously, such as sitting through an activity but not engaging fully, was embraced by the clowns.

Older people enjoy caregiver roles: Older people in care homes, many of whom had been caregivers in their lives, enjoyed the opportunity to take care of the clowns.

Slapstick techniques, like falling over and being clumsy, resonated well with this group, as they eagerly participated in assisting the clowns.

Props matter: While clowns work with problems and mistakes, the choice of props and the environment’s setup should be carefully considered.

Older people with dementia often have strong preferences and judgments about their surroundings, which can affect their participation.

The clowns realised that poor lighting, for example, could discourage participation in certain activities.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaitė – NARA

Nina Sabo and Petra Bokić are experienced healthcare clowns working in Zagreb and Rijeka, Croatia, with CRVENI NOSOVI Klaunovidoktori.

The Croatian RED NOSES organisation already had long-standing experience performing for children with disabilities more generally with the Travelling Caravan Orchestra performance, and therefore also a strong network of day centres, kindergartens, and schools that they visited.

Petra had many years of experience with the CarO performance, whereas Nina started performing CarO just after a year of working with the ClowNexus project.

Given the specific focus of ClowNexus on ASD, in the framework of the project, the two worked as a duo, visiting children on the autism spectrum in Bajka Kindergarten and a day care center at the Zagreb Autism Center.

The same Centre agreed to host ClowNexus clowns working with children with ASD from across the project countries as part of the last International Learning Laboratory of the project, in January 2023.

You can read more about this particular laboratory and see some photos from the five-day event in the ClowNexus blog.

The Croatian clowns visited the two institutions monthly, seeing the children for two or three days in a row.

The visits took place over a year and around eight months.

Nina and Petra worked with a teacher and rehabilitator in Bajka Kindergarten to identify two groups to work with, which changed in the new school year.

In the Centre for Autism, they visited all six groups of children going there at the time, seeing some in one visit and others in another. All the children they visited were autistic.

The Croatian artists gathered information about the needs of the children they worked with in conversations with the staff – administrations, teachers, and professional therapists, as well as in reflections between the duo partners and in consultation with the artistic leadership in the organisation.

Learning through exploration – a process that is ongoing for all healthcare clowns but particularly pronounced in the ethos of the ClowNexus project – was a major source of learning for the Croatian artists. In the words of one of them:

“In order to develop a successful collaboration with children on the autism spectrum, it was necessary to learn more about how they perceive the world. Only then can we develop mutual understanding and joyful interaction.”

The clowns initially gathered information on the specific children they were seeing, including names, pictures, progress, and difficulties, and any new developments from the rehabilitators working with them.

After the initial visits, the clowns no longer solicited this information, both to avoid burdening the staff and because they gained new confidence in finding things out for themselves.

Furthermore, the information provided was not always in line with the clowns’ experience of working with the specific children, and it was not helpful for the clowns to be aware of the array of issues experienced by the children in the course of their visits.

The clowns felt comfortable relying on their intuition, which later replaced the theoretical information on the children.

Below follows a description of how the Croatian artists’ work addressed the needs of different target groups, including the clowns and their organisation.

Children with ASD: In an interview on the experience with the CRVENI NOSOVI clowndoctors, Zagreb Autism Center’s director noted various benefits they bring for the children.

She noted the clowns have a way of reaching the children, who open up to the clowns, are happy and relaxed in their presence, and how beneficial this is for their emotional development.

She also noted how aligned the clowns’ approach – their varied means of communication including through touch, gesture, and gaze – is with the centre’s way of working, and how important it is to know that the clowns are exploring new ways to connect with children on the spectrum, a growing group.

Institutional carers: Also from accounts of the Zagreb Autism Centre’s director, the clowns’ work and their relaxing and joyous effect on the children open up space for easier teaching, improving, and adding value to the work of the institution.

Family carers: Family carers, as in most cases when working with children in day care institutions, were not accessible to the clowns as they were not present at the time of the visits.

Clown duo: Through the co-creative exploration and development of their own unique format to work with children with ASD, the Croatian clowns, on the one hand, learned a lot about their universe, but on the other hand, learned to unlearn.

In the words of one of them: “When you think you’ve got it, you understand, you know what to do and how to do it, and get too cocky – the universe will show you that you know nothing!”

Healthcare clowning organisation: CRVENI NOSOVI Klaunovidoktori have among the most experienced clowns in the RED NOSES network, many also with specific experience working with children with disabilities in different capacities.

The ClowNexus project helped to bring more depth and direct specific focus to the project’s target groups and reflection on what works.

In the autumn of 2023, as part of the multiplication of learning foreseen in the project, participating clowns including in the ASD and Dementia tracks, as well as outside lecturers, delivered an organisation-wide several-day workshop focused on sensory clowning and tools.

© Mindaugas Drigotas, Berta Tilmantaitė – NARA

The Croatian clown duo used the entrance with a parade and a suitcase filled with musical instruments and other magical objects as the frame for their visits, introducing a variation of different tools within this frame.

Scenario in Focus: The magic, musical suitcase & suitcase of elements

Why interesting: The scenario took as a departure point an existing Red Noses format – Traveling Caravan Orchestra, and maintained several of its elements, including entrance with a parade and a mysterious suitcase housing objects from a theme for that given day.

The suitcase element and the mystery and surprise it represents has the power to create one of those rare connections in such settings for children to all focus on the same activity.

While using a familiar format for inspiration, the participating Croatian artists developed their idea to pilot and incorporate elements from nature and the cycle of life, varying focus between music and sound to touch and feel.

Intention: To awaken interest, disrupt the regular routine, and create a group connection.

Who participates: Children, staff present in the room (rehabilitators), the clown duo.

Duration: Varies for up to 30 minutes.

Setup of the space: The children are in their regular surroundings, each in their own activity at the time the clowns enter, and then focus or drift off freely.

Artistic skills needed: Playing instruments; singing; movement & slapstick; creating with an object; playing with voice and sound.

Props: Suitcase, fabric/scarves; musical instruments; elements to roleplay with – for example, the suitcase of elements contains golden fabric to represent the earth; an egg to represent a seed to be planted; a bucket and bubbles to represent water; and a yellow scarf to represent the sun’s heat needed for the seed to grow.

Description: Clowns enter with a parade, making rhythm and music, carrying a suitcase. They use a simple repetitive “hello song.”

Upon arrival, the intention is to get the children interested in the mysterious content of the suitcase, as there is a surprise in there for all to discover.

In a sense, it’s to get them to focus on one organised activity, huddling for the unraveling of the secret of the day.

The clowns and the children get together as a group, as there is one object that is getting all the attention – the suitcase.

Being together as a group and participating together in the same activity is very rare for the children.

Slowly begins the ritual of opening it – knocking on it, asking if we can open it, the suitcase saying no, and giving different tasks – knock 5 times, clean me with a scarf, blow on me, sing a melody…and then it opens.

Inside are the objects for the theme of the day. Sometimes the suitcase contains musical instruments for the kids to play with; other times it can be filled with natural elements, seeds to plant in the earth, different sensorial objects.

The clowns invite the children to touch and play with the objects, balancing between facilitating the children’s engagement with the objects and letting them freely explore and play with what’s there and the clowns.